Turkey: the Disruptive Ally? By Nicholas Williams (Vice President of CERIS), 24 November 2022 (PDF)

> Nicholas Williams, OBE is a Senior Associate Fellow for the European Leadership Network (ELN). He was a long-serving member of NATO’s International Staff, most recently as Head of Operations for Afghanistan and Iraq. Prior to this, Nick served in senior positions in NATO, EU, and British missions in Afghanistan, Bosnia Herzegovina, and Iraq. He began his career in the British Ministry of Defence working on defence policy and planning issues, with multiple secondments to NATO functions during the Cold War and to the French Ministry of Defence in its aftermath. Mr. Nicholas Williams is the Vice President of CERIS-ULB Diplomatic School of Brussels since 2021.

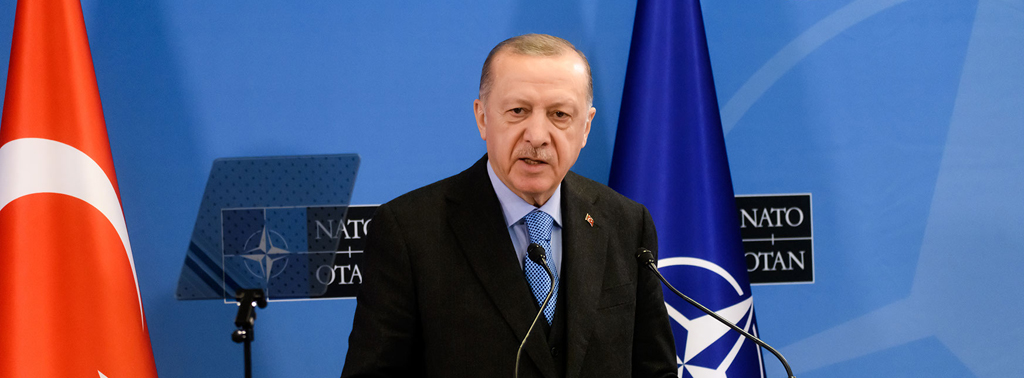

An article in the New York Times in May 2022, referred to Turkey as a “disruptive ally”. It was looking ahead to NATO’s June Summit in Madrid and fearing that Turkey would veto an otherwise smooth process of Finland’s and Sweden’s accession to NATO. In the event, Turkey agreed that Finland and Sweden should be invited to join NATO. This followed a tough trilateral negotiation where a highly demanding President Erdogan placed tough pre-conditions on President Niinistö of Finland and Prime Minister Andersson of Sweden. Their Foreign Ministers then signed a memorandum addressing Turkey’s security concerns in relation to Kurdish terrorism, paving the way for Finland’s and Sweden’s NATO membership.

On the face of it, it was a triumph for President Erdogan. He achieved everything he wanted; a commitment to facilitate the extradition from Sweden and Finland to Turkey of Kurdish activists accused of terrorism; a highly visible fist-bump with President Biden, thus demonstrating at home his stature as a global statesman who cannot be ignored; and a US commitment to rethink its embargo on the sale of F-16s to Turkey.

In addition, even though Turkey, in accordance with NATO treaty procedure, alongside the 29 other allies, formally invited Finland and Sweden to join NATO, their actual membership depends on one final step: the agreement by all 30 member parliaments. Only Hungary and Turkey have yet to ratify. The Turkish parliament, under the watchful sway of President Erdogan, will consider very carefully whether Turkey’s highly exigent interpretation of the trilateral memorandum has been fulfilled, particularly by Sweden, where he considers that “terrorists are roaming freely.”

Would a Turkish parliamentary veto matter? After all, as Turkish diplomats point out, Greece held up North Macedonia’s membership of NATO for nineteen years, over what all other allies considered a trivial and easily resolvable dispute over the country’s name. On the contrary, they say, Turkey is objecting to something much more significant and life-threatening: terrorism within and just beyond its borders. As the bomb attack in Istanbul on 13 November 2022 proved, the terrorist threat to Turkey is real and persistent. It is quite legitimate for an ally to object to the membership of a country which does not meet the criteria of membership and has an allegedly lax approach to terrorism. After all, NATO in its new Strategic Concept, also agreed at June’s Madrid Summit, considers terrorism as one of the two threats facing the Alliance, alongside Russia.

Nevertheless, the accession of Sweden and Finland matters a great deal to NATO, and particularly to the United States. Without them – that is to say, without the hinterland and springboard that Sweden and Finland would provide to NATO’s military planners – it would be difficult, exorbitantly costly and probably impossible to defend the three exposed Baltic states on NATO’s north-eastern flank. Northern European allies are all adamant in wanting to see the speediest possible and full integration of the two Nordic countries into NATO’s strategic defence planning. The United States is equally keen. At a time when the United States is facing up to its Chinese strategic competitor, it would like the significant assistance that Sweden and Finland can contribute to NATO’s regional defence against Russia. The more that the Europeans can do to defend themselves regionally, the fewer military resources the United States will have to commit to NATO’s defence. Both Swedish and Finnish membership of NATO is therefore within the logic of the US “pivot” towards Asia.

As for Russia, Turkey’s position in NATO is not so much disruptive as what could be called anomalous. All Summit leaders, including Erdogan¹, agreed in Madrid that Russia is “the most significant and direct threat to Allies’ security”. By putting Turkey’s fight against Kurdish terrorism as its absolute and only priority in relation to the membership of Sweden and Finland, it relativises the threat from Russia. Moreover, it gives the impression that the Russian problem is of passing concern. Unlike all other allies, Turkey has not imposed sanctions, and Erdogan even held a Summit with Putin in Sochi in August 2022, at the height of Russian military success, with the aim of boosting trade between the two countries. Other allies understand that Turkey has to perform a difficult balancing act between Ukraine and Russia, and is even helpful, as a Black Sea intermediary, between Russia and Ukraine. Nevertheless, they consider it inconsistent and paradoxical for Turkey to be so demanding in relation to membership of Sweden and Finland, but so understanding in relation to Russia, the “most significant and direct threat” to NATO.

The episode of Turkey’s resistance to Swedish and Finnish membership of NATO is an outward and visible sign of a profounder shift in Turkey’s geo-strategic position. The arguments for Turkey being an asset to the Alliance are well known², but need to be updated. In the Cold War, Turkey’s geographical position, with a border with the Soviet Union, ensured its value to the Alliance, most significantly as a bulwark of the southern flank. The strategic value of the Black Sea in bottling up Russia has replaced it. And as Daalder, a former US Ambassador to NATO, argues, Turkey still retains its strategic importance for access to and stabilisation of the Middle East.

But Erdogan’s threats to Greece (Turkey “can come suddenly one night”) is a sign that he is willing to contemplate the unthinkable: an attack of one ally against another. That would mean an irrevocable break with the US, Alliance generally and the European Union. There is an argument that next year’s presidential elections in Turkey are provoking Erdogan to talk tough, after which, should he win, he will revert to Turkey’s traditional judicious balancing of its European interests against its Asian and regional preoccupations. For the sake of NATO and Turkey – and not least Greece – let us hope that this is true. Otherwise, the consequences would be truly disruptive.

____________________

¹ Madrid Summit Declaration, issued by Heads of State and Government, paragraph 5, 29 June, 2022